A Different World

Fall 2019's Bodies & Identities in Contemporary Cuba course—and its subsequent week-long trip to the island nation—demonstrates the transformative potential of short-term study abroad.

By Meghan Kita

This article orginally appeared in the Spring 2020 issue of Muhlenberg Magazine.

On their first full day in Havana, the 18 Muhlenberg students and two professors who traveled to Cuba over winter break encountered a scene out of a stock image of the city: a line of enormous and colorful American cars from the 1950s. The drivers waited outside the José Martí Memorial, a towering structure that offers visitors panoramic views of the city, knowing that tourists love to take pictures with—and pay for rides in—these classic cars.

“We had talked about this in class,” says Janine Chi, associate professor of sociology, who co-teaches the Bodies & Identities in Contemporary Cuba course with Cathy Marie Ouellette, associate professor of history. “We had read several articles about America’s longing for Cuba to be stuck in the past or the Americans’ picture of the past in Cuba, pre-revolution: rum, dancing, girls...the Tropicana, which is still there. The students were happy to critique that in class, pooh-poohing all of it.”

But as the group walked to the bus, Chi and Ouellette noticed almost all the students snapping photos of the cars. Some even went over to pose with them, though they wouldn’t be able to share the images until their return to the United States—their phones didn’t work in Cuba, and the task of finding reliable WiFi was not built into the week’s packed itinerary. On the bus, Chi called them out. The students looked sheepish.

“That’s when they realized that it’s one thing to read something and get wrapped up in the theory, but it’s another thing to see themselves in action,” she says. “I said, ‘The thing is for you to recognize when those moments are happening. It’s for you to now be able to reflect back.’”

ACADEMICS ABROAD

Reflection is a key component of all the College’s integrative learning courses, a designation bestowed on courses that require students to examine the subject matter from at least two distinct perspectives. Since 2017, Muhlenberg has required all students to complete at least one integrative learning course in order to graduate, recognizing that exposure to a range of perspectives and disciplines is the core of a liberal arts education. Muhlenberg Integrative Learning Abroad (MILA) courses, of which Chi and Ouellette’s Cuba course is one, predate that revision to the curriculum—the first MILAs took place in 1999.

“Even before we had the integrative learning designation, MILA courses were one of our greatest examples of integrative learning,” says Dean of Global Education Donna Kish-Goodling.

All MILAs involve a semester of learning at Muhlenberg and a one- to three-week period spent off-campus with faculty. The majority are team taught, like the Cuba MILA, and many take place every two or three years (Chi and Ouellette first took students to Cuba in January 2018). Still, the differences between MILAs far outnumber their similarities.

“The MILAs span science, social science, the humanities and the performing arts,” Kish-Goodling says. “You don’t have to participate in one that’s your major—they’re open to non-majors. They allow students to broaden their entire liberal arts experience. And, MILAs give an alternative for students to get an abroad experience without having to go for an entire semester for academic reasons, athletic reasons or personal reasons.”

Americans live in such a global world of comfort. We’re not multilingual. We don’t try to be multilingual. We don’t know how to embrace and experience the rest of the world. If you prepare students and take them to places they wouldn’t go on their own, then you teach them how to engage with the world.

Cathy Ouellette

Many MILAs offer the opportunity to learn about and travel to places in the “Global South,” Ouellette says, meaning the low- and middleincome countries in Latin and South America, Africa and southern Asia. (See “Upcoming MILAs at a Glance,” page 45, to learn about the four other MILAs being offered this year.) Students who spend a full semester outside the United States more frequently select destinations that are in Europe, where 84 percent of those students chose to study during the 2018-2019 academic year.

“Americans live in such a global world of comfort. We’re not multilingual. We don’t try to be multilingual. We don’t know how to embrace and experience the rest of the world,” Ouellette says. “If you prepare students and take them to places they wouldn’t go on their own, then you teach them how to engage with the world.”

INSIDE THE CLASSROOM

Cuba is an increasingly difficult place to go on one’s own: Americans have been able to travel there since 2015, but the Trump administration has taken steps to restrict access (by banning cruise ships from docking there, for example).

Andrea Kayla Rodriguez ’21, an international studies major with minors in Latin American & Caribbean studies and Spanish, was aware of the country’s reputation: “Prior to this course, the only things I knew about Cuba were obviously about the revolution and Fidel Castro’s time in power, the dictatorship, the typical U.S. narrative that Cuba is evil because of its socialist system,” she says. “You’re not supposed to travel there because it’s dangerous.”

Chi and Ouellette spent the fall semester challenging that narrative in the classroom, approaching Cuba’s last century of history and its present-day reality from two distinct (and sometimes divergent) perspectives—that of a sociologist and that of a historian. For example, the two disagreed on the merits of a documentary about Cuban rap they watched with the students, and the students, in their reflection papers, ended up equally divided.

These moments of opposition are, in a way, the point of all Muhlenberg’s integrative learning courses...and they often make students squirm. “For me, that discomfort—recognizing it on a student’s face or in their words—is what we’re in the classroom for,” Ouellette says. “That is a real moment of acknowledgment that there is no one fixed answer.”

“There’s no specific right answer. There are better answers,” Chi adds. “When you’re teaching your own course, you’re assuming everyone else thinks the same way you do. You don’t even realize the training you’ve had until you encounter someone who’s been trained differently. Then, you’re forced to deal with the idea that you’re looking at something from a point of view.”

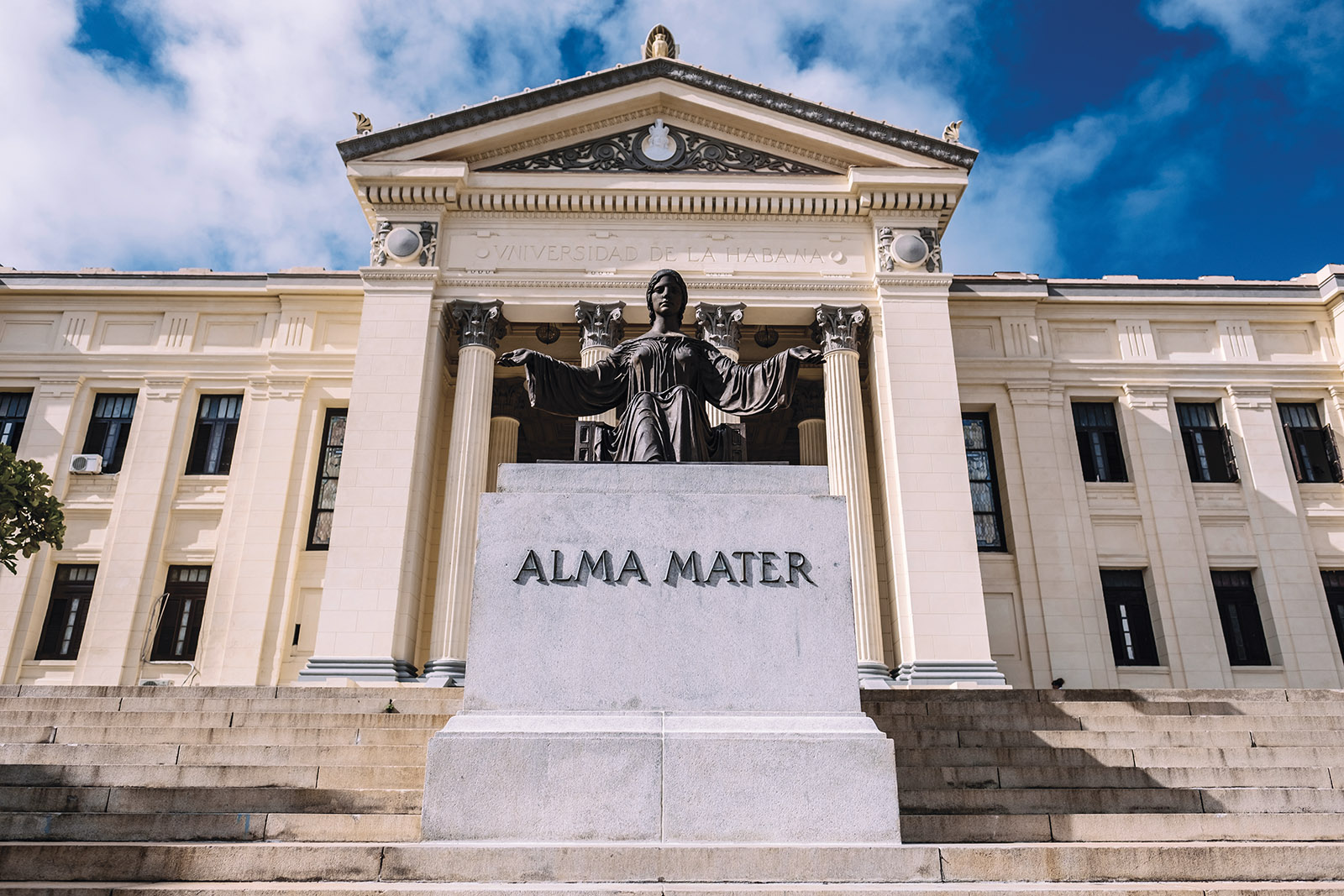

In Cuba, Muhlenberg students toured the University of Havana and attended lectures from some UHavana professors, who are all employees of the state. Education at the university is free to citizens who take a series of standardized tests. Every province in Cuba has universities.

CUBA TODAY

By the end of the semester, students had more awareness of the American point of view and its effect on their own knowledge and beliefs about Cuba. But traveling there, and actually being able to see the systems they learned about in class in practice, gave them a rare perspective: that of Americans who’ve been educated about Cuba well beyond the traditional U.S. narrative who’ve also spent time in the country.

For a week, the students lived with Cuban families in homestays set up by the Council on International Educational Exchange (CIEE). (Approximately 20 percent of MILAs utilize homestays, Kish-Goodling says.) With their host families, they got to see some cultural norms they’d learned about in practice.

“We had talked in class about the fact that in Cuban families, it’s normal to live with multiple generations,” says Nicholas Blue ’20, a history major and business administration minor. “The couple we stayed with owned the building they lived in and had four generations of their family living there. That sense of community was so different from how we see the concept of family in the United States.”

The subject matter of the Cuba MILA course uniquely prepared the students to make such observations: While many other MILAs are hyperspecific (for example, the Costa Rica MILA focuses on sustainability, the Ireland MILA on theatre and creative writing), this one is about what it means to live in Cuba today and the history that shaped its modern culture and society.

“Having the academic component allowed us to see what’s happening in Cuba a little more critically,” says Lisha Rabeje ’21, a sociology major. “A lot of things there are state-censored. Sometimes what they say isn’t what’s really happening for some populations, particularly for AfroCubans. The coursework allowed us to be more mindful tourists and see what we studied come to life on the trip.”

UNIQUE CHALLENGES

The Cuban government’s control extends into the itineraries of educational trips such as this one. It requires CIEE to hire Cuban guides to accompany and interpret for each group.

“Cuba is remarkably different from other MILAs in that it requires an extreme degree of flexibility,” Ouellette says. “The state has to approve every request we make. Often what that means is: We will have a verbal agreement with a lecturer and then, as we’re entering the classroom at the scheduled time, someone else appears.”

That happened on this trip, with no advance notice and no explanation provided. Another day, the group had arranged to visit the Cuban National Center for Sex Education, and 20 minutes before their scheduled arrival, their tour guide received a telephone call saying the visit was cancelled.

Still, the bulk of the itinerary took place as planned, including stops the average tourist would not likely make. For example, the group visited Los Pocitos, a neighborhood on the outskirts of Havana where resources are even scarcer than they are inside the city. Students saw a community garden with raised beds built from discarded bottles and planters made from halved cans.

“It took students a while to understand that most of the pollution you see deposited along this river, which is the only access of potable water for that community, it wasn’t from the community members themselves. It comes from Havana, and it all ends up here,” Ouellette says. “They had a revelation about how communities that are not formally incorporated into any urban area are left to fend for themselves, for even what we consider the most basic necessities.”

“Sometimes, it takes scarcity to become resourceful,” Chi adds. “We talk about recycling, but we put it in a blue bin—we’re not repurposing, not reusing, not doing something with it.”

The group also visited Memorial de la Denuncia, a new museum chronicling the history of U.S. aggression toward Cuba since 1959. The museum displayed archival footage of some of the more than 800 times the CIA attempted to assassinate Fidel Castro, video that’s not available in the United States. These attempts were described as “terrorism,” a word that American students aren’t accustomed to seeing applied to the actions of their own government. A couple of students cried, Ouellette says: “They experienced a great deal of hospitality from their host families. How Cubans feel about the U.S. government versus how they feel about Americans was palpable to them.”

Ji Ku ’20 (in foreground), a physics major with a mathematics minor, takes notes while visiting Trimvato, a former African slave plantation in Matanzas, Cuba. It was the site of a series of slave rebellions led by an enslaved Yoruba woman named Carlota in 1843.

SHIFTING PERSPECTIVES

Developing this kind of awareness of how another part of the world sees the United States is a goal of all study-abroad programs, Kish-Goodling says. The part of the world explored in this particular MILA has been largely cut off from the American experience—and vice versa—for decades.

Still, what one University of Havana professor told the class rang true for Rodriguez, the junior studying international relations: “Our ways of life aren’t so different. We just have access to different rights.” Cubans may not enjoy the First Amendment rights Americans do—freedom of speech, of assembly, of press—but they have access to universal healthcare, free education and government-guaranteed employment, Rodriguez notes. Value judgments of what’s better or what’s worse are inherently shaped by one’s own point of view.

“I realized that, as a global citizen, I wasn’t doing my part,” she says. “I wasn’t making the effort to understand other people’s ways of life. I was following the U.S. narrative of criminalizing everything that wasn’t us.”

Many students had similar revelations, say Chi and Ouellette. When the group met on campus at the beginning of the spring semester, they discussed everything that seemed different in Cuba—for example, the housing system, in which the state sets the value of land and property— and the parallels that could be found in the United States (like rent-controlled apartments in New York City). Not only had the students gained awareness of how Cubans see the United States, their own perceptions of their home country had changed.

“This experience was challenging in the sense that it forced the students to reexamine their own systems when faced with a different system,” Chi says. “And one of the things they learned is that these are all imperfect systems.”