I Speak Spanish. I Can Help!

Spanish-English poll interpreters are legally required at the majority of Lehigh County’s precincts. Since 2004, Associate Professor of Spanish Erika M. Sutherland has been training interpreters for presidential elections.By: Meghan Kita Friday, October 30, 2020 09:49 AM

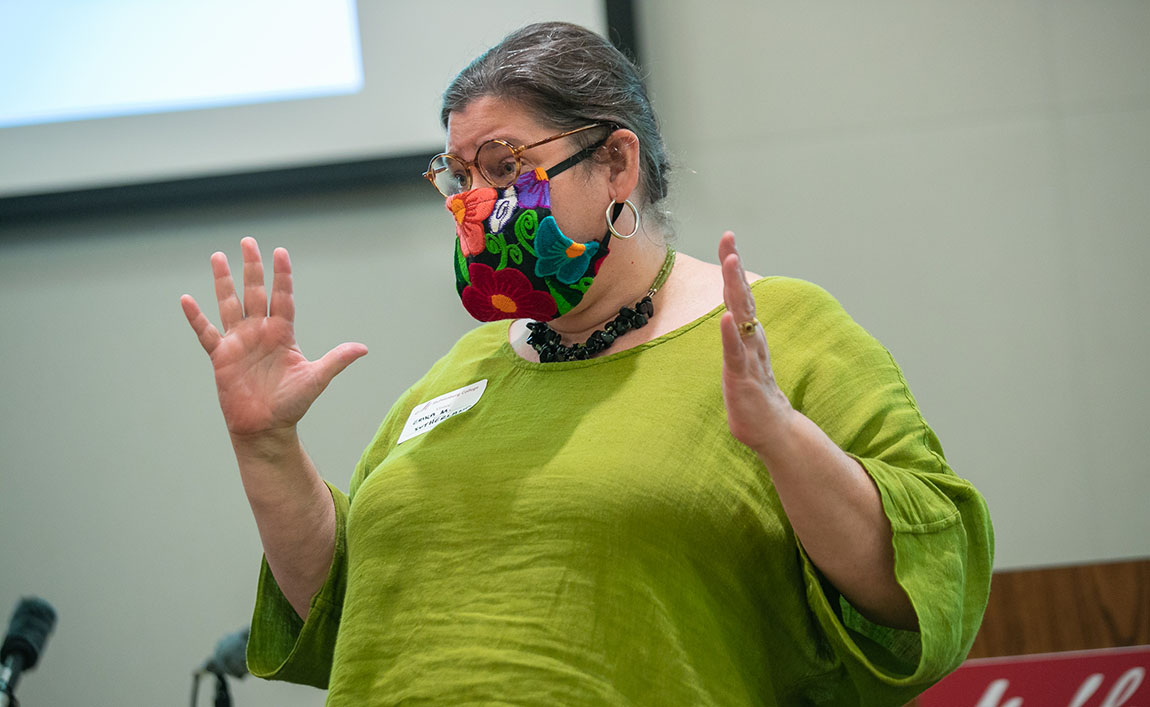

Associate Professor of Spanish Erika M. Sutherland (in green, at left) leads a training for poll interpreters on October 23, 2020. Photos by Marco Calderon.

Associate Professor of Spanish Erika M. Sutherland (in green, at left) leads a training for poll interpreters on October 23, 2020. Photos by Marco Calderon.On Tuesday, Associate Professor of Spanish Erika M. Sutherland will be on call for the more than 90 bilingual poll interpreters she trained to work this Election Day. She plans to spend lots of time in her car, picking up donated food from restaurants (many of them immigrant-owned) in downtown Allentown and delivering it to the Lehigh County polling stations where her trainees are working. At some of those stations, she anticipates needing to intervene when fellow poll workers question the interpreters’ presence.

“A lot of the poll workers are retired people who have been doing this for many years. They haven’t necessarily changed even as demographics have changed,” Sutherland says. “Poll workers sometimes think [interpreters are] an add-on or an unnecessary nuisance. The interpreters are challenged on a very regular basis. But this is not a voluntary thing—it’s a federally sanctioned part of the law.”

Sutherland is referring to the Voting Rights Act, which requires all precincts in which more than 5 percent of registered voters are of limited English capacity to provide poll interpreters bilingual in English and that population’s language. Ninety-seven of Lehigh County’s 161 precincts have enough Spanish speakers to require poll interpreters.

This year presented some challenges due to COVID-19—for example, many of the students Sutherland would normally work with from local colleges (including Muhlenberg) aren’t necessarily living in the area. But even in non-pandemic years, the majority of the interpreters she trains are immigrants from the community, many from El Grupo de Apoyo e Integración Hispanoamericano, the support group for Hispanic immigrants in the Lehigh Valley that Sutherland has been running since 1999.

“There’s a really strong interest in the immigrant community in being as involved as possible, even if you’re not able to vote, and a strong interest among college students to use their Spanish in a real-life setting,” says Sutherland (pictured above). “This is a place where the two groups come into perfect synchronicity.”

Sutherland, who has been training interpreters for presidential elections since 2004, says about a third of each training session revolves around Election Day details—how polling locations are set up, how the machines work, what is and isn’t allowed—while the rest is “more about the sociologistics of it all.”

For example, Hispanic voters often have two last names, and if the poll worker checking the registration looks up the wrong one, they may erroneously turn the voter away. Sutherland says Hispanic names are also subject to frequent typos on official identification—Vs and Bs are transposed, or Ss and Zs.

“An interpreter is trained to be attentive to that possibility, to step in and say: ‘The addresses are matching up. You just have a typo,’” she says. “They’re trained to recognize when there’s a debate so they can intervene.”

At the training sessions, trainees also receive T-shirts to wear to the polls that say, “Hablo español. ¡Puedo ayudar!” (“I speak Spanish. I can help!”) This small investment goes a long way, Sutherland says: “When voters come into the precinct, the first thing they’re going to see is someone in a bright red shirt that says something in Spanish. They’ll know immediately that this is someone who’s friendly, who’s an ally and who speaks Spanish. That friendly presence is really of incalculable value.”

Professor and Chair of Biology Marten Edwards went through Sutherland’s training this year for the first time after starting his journey to learn Spanish five years ago. He’s looking forward to using his newly developed skills for an important cause.

“I know how confusing it can be to find myself in a place where nobody speaks English. I am tremendously grateful for this opportunity to help others feel at more home here in the Lehigh Valley and not worry about asking questions,” says Edwards, pictured. “Voting this year during a pandemic is going to be confusing and stressful enough—even without a language barrier.”

“I know how confusing it can be to find myself in a place where nobody speaks English. I am tremendously grateful for this opportunity to help others feel at more home here in the Lehigh Valley and not worry about asking questions,” says Edwards, pictured. “Voting this year during a pandemic is going to be confusing and stressful enough—even without a language barrier.”

Not all Spanish-speaking voters in Pennsylvania will have this level of assistance available. For example, Berks County relies on phone interpreters. A voter with a question must go up to the precinct judge—who may or may not speak Spanish—and request a phone interpreter, an experience Sutherland describes as “horrifically intimidating.”

“They’re meeting the letter of the law, but definitely not meeting the spirit of the law,” she says of the neighboring county. “Lehigh County does a pretty good job in doing their best to provide in-person interpreters.”

In past years, Lehigh County has trained interpreters with only the standard poll-worker training on how to work the machines, what to expect on Election Day and the rules of engaging with voters. This year, all Lehigh County interpreters are receiving Sutherland’s specialized preparation for the specific challenges that Hispanic voters are most likely to face. The decision to have Sutherland lead the training for all interpreters is a response to what Erika Jufre of the Lehigh County Electoral Board (pictured above) has noticed: that some of the county-trained poll workers (including interpreters) fail to show up on Election Day, but Sutherland’s trainees always do.

“We’re creating that buy-in, that sense of urgency that they’re really needed there, that they’re really crucial to the functioning of democracy,” Sutherland says.