The Polling Place

Muhlenberg Magazine features the College's Institute of Public Opinion, which gives students hands-on experience that shapes political discourse and community action.

In the call center in the basement of Trexler Library, headset-wearing students sit at three of the 12 computers. It’s a Friday afternoon in mid-September. Between the recent congressional redistricting, a handful of big-deal races and the fact that Pennsylvania just barely went red in the last presidential election, the state’s political climate is drawing national and international attention, and today’s survey is about the upcoming midterm elections.

Despite the hoopla, this shift is quiet because many student workers have class at this time. Plus, the folks they’re trying to reach (voting members of the Pennsylvania electorate) are more likely to answer their phones during the evening or weekend operating hours of the call center, when more students might show up to work than the room can accommodate.

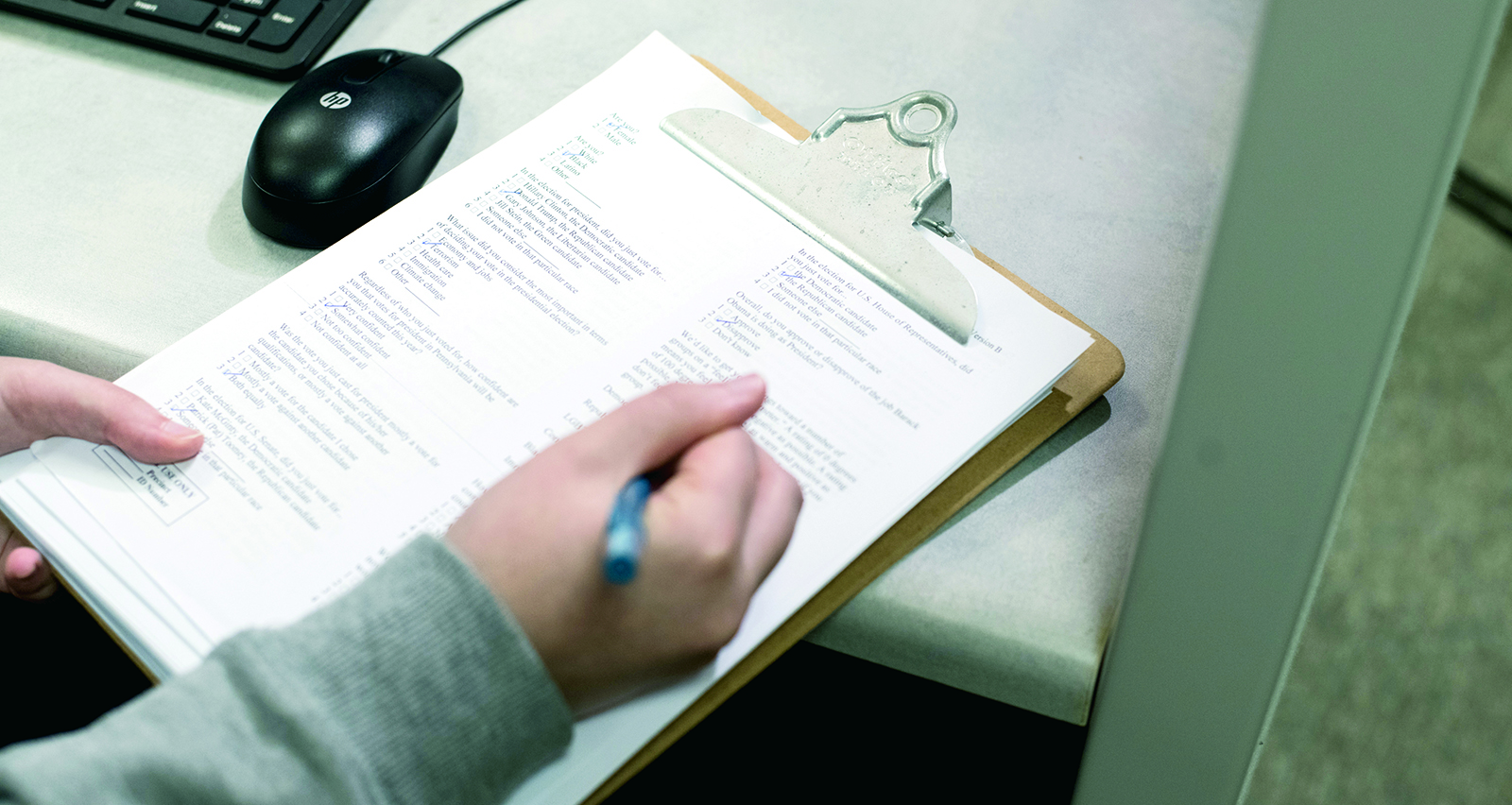

The workers who are here call numbers randomly generated by WinCati, the computer program that displays the questions and records responses. If someone doesn’t answer—an increasingly common occurrence in this age of spammy robocalls—the student leaves a message to say they’re calling from the Muhlenberg College Institute of Public Opinion (MCIPO) to conduct a survey and that they’ll try again later. This happens several times.

But then, some excitement: Two students get someone on the line simultaneously. After confirming the people are registered to vote in Pennsylvania, the students ask how likely the people are to vote, their opinions on the performance of various politicians, which issues matter most to them and a number of other questions. Both respondents happen to be chatty; the interviewers tally their responses and listen politely as they elaborate. Within 10 minutes, the students have added to a pool of data that will contribute to an understanding of the public’s take on key issues, political and otherwise.

The MCIPO—known around campus as simply “the polling institute”—is nearly as old as some of the students making the calls. The first surveys took place in the fall of 2001, a year after the institute’s founder and director, Professor of Political Science Chris Borick (pictured below), came to Muhlenberg.

“Like everything at Muhlenberg, the goal was to have a student focus,” Borick says. “Students would play a primary role in the management of the institute, students would take on ownership of projects and various functions of the institute and the data would contribute to academic study.”

Today, the institute has a national reputation: It recently earned an “A” grade from the well-known analytical site FiveThirtyEight, and CNN referred to it as a “gold standard pollster.” But even as the scope of the institute’s research has expanded, as it has forged partnerships with institutions large and small and as it has garnered national attention for itself and the College, students and alumni can attest that it has remained true to its student-centric mission.

Calls to Action

With oversight from Borick, students manage many of the day-to-day operations of the call center that collects the institute's data. In any given semester, there will be about 50 interviewers, five or six supervisors and one or two assistant directors.

The interviewer role attracts students of all majors who seek flexibility: You show up whenever you want during the 22 hours the institute is open each week and work as much or as little as you want.

“What happens to a number of those students is their experiences lead them to want to get more engaged with the institute,” Borick says.

Prianka Hashim ’19 (pictured below), a neuroscience major and women’s & gender studies minor, is one of those students: She was interested in the U.S. political climate her first year, in the lead-up to the 2016 presidential election, so she worked quite a few hours conducting interviews. The student management team noticed her dedication and asked her to join them her sophomore year. Last year, she became an assistant director, a role she’s sharing this year with Jordan Zanetti ’19, who held the role last spring as Hashim studied in Copenhagen.

“I started at the polling institute thinking I’d check it out, and I never left,” Hashim jokes.

The student supervisors and directors have set hours, since a member of the management team is always there while the call center is open. These students do it all: They get new interviewers established as College employees, they train new interviewers on how to conduct the surveys and work with the technology, they handle payroll and they respond when there are problems with the phones or computers. Some even help to program the surveys and analyze the results.

Surveying the Surveys

“When we started, we said, ‘Look, we’re not going to be a gigantic research organization that does everything. We’re not designed for that,” Borick recalls. “‘We’re a small liberal-arts college. We want education and the student experience central to the institute.’”

The plan was to focus on local and statewide surveys, and that still makes up the bulk of the research that takes place there. The institute has a number of Lehigh Valley partners, such as The Morning Call, the Allentown School District and the Bethlehem Health Department, that can request that the institute conduct a survey to help inform their reporting or policy.

The institute also teams up with classes to gather information that pertains to a course’s subject matter. For example, Borick teaches a linked course with Psychology Professor Mark Sciutto called Mental Health: Science and Public Policy. The students in their classes—Public Health Policy and Abnormal Psychology—design questions, work in the call center to execute a statewide survey and then analyze the results.

That said, the institute does conduct some national surveys, most notably on the subjects of climate change and energy policy. Borick had researched and written about environmental policy with colleagues at the University of Michigan, and in 2008, the two institutions teamed up on a national poll. The students and faculty from Michigan provided the policy expertise and the students and faculty from Muhlenberg provided the polling expertise.

“When we did it, we recognized how important it would be to make this a longer term project,” Borick says. “There aren’t too many partnerships between high-end research institutions like Michigan and quality liberal arts colleges like Muhlenberg. It’s one that’s been really productive over the years.”

“The partnership gives us an opportunity to work with Chris Borick, who brings not only survey research expertise but also a deep understanding of electoral and climate politics,” says Sarah Mills, senior project manager at Michigan’s Center for Local, State, and Urban Policy. “The business model of the Institute for Public Opinion, offering high-quality research at a very low cost, has really enabled us to sustain this research over time.”

A Unique Resource

Not only is such a partnership rare, so is having access to—and hands-on experience with—a well-respected public-opinion polling center as an undergraduate. Sarah Niebler ’04, a political science and philosophy double major, got to enjoy those benefits as she worked on her honors thesis with Congregations United for Neighborhood Action, a community group in downtown Allentown.

“Borick let me ask some questions on surveys the institute was doing locally that pertained to my own research,” says Niebler, who’s now an assistant professor of political science at Dickinson College. “The fact that Muhlenberg has an institute like this allows for students to do research that is not possible everywhere. The cost could be so prohibitive to do a national survey or even a statewide survey elsewhere, but the infrastructure exists to do them at Muhlenberg. That students get to put questions on those surveys? It maybe happens at some of the Ivies, but I’m not even sure about that.”

And the benefits aren’t limited to those who are political science majors: Students of all disciplines work at the institute, and many find ways to apply what they’ve learned there to their own studies.

“The polling center definitely shaped my interest in doing independent research,” Hashim says. She’s pursued research projects with Stanley Road Professor of Neuroscience Jeremy Teissere, as well as Associate Professor of Psychology and Director of Women’s & Gender Studies Kate Richmond, and she plans to take a gap year between Muhlenberg and medical school to work in a lab.

Beyond the Institute

Steven Fischer ’06, a political science major who conducts market research for higher education institutions, uses the skills he developed during his time at the polling institute on a regular basis.

“I learned from Professor Borick the best way to design a survey without bias, which is critical in this field,” Fischer says. “If you ask a biased question and you get an answer, you don’t know whether that’s the real answer or not.”

The fact that institute alumni have applicable skills matters in academia as well: After graduation, Kathleen Rogers ’14, a political science major and women’s & gender studies minor, entered the political science Ph.D. program at Rutgers University. Because of the four years she spent at Muhlenberg’s polling institute, she was asked in her first year to work at the Rutgers University Eagleton Center for Public Interest Polling—an opportunity usually reserved for second- or third-year grad students. Her time as an interviewer and supervisor at Muhlenberg also enhanced her understanding of her coursework.

“It was really helpful for me to know the process through which data is collected,” she says. “A lot of people in my program don’t think too much about the fact that these are usually students calling and conducting these surveys or about how the questions are asked and how that might sound on the phone. It gives me a bit more context for some of the data I’m looking at now.”

Niebler, who was one of the institute’s first crop of interviewers in 2001, returned after graduation as a Lehigh University Community Fellow during the Bush-Kerry election. She remembers helping to conduct a number of surveys and to host a public debate screening with a Q&A session afterwards.

“That was my first taste of what it would be like to be a political scientist during a presidential election year,” she says. “I got to watch Borick do that in 2004, and then I was being asked to do a lot of the same things at Dickinson 12 years later.”

Change and Mission

The focus this fall has been on capitalizing on the interest in the 2018 midterm elections: The stars aligned to put Pennsylvania at the epicenter of this political cycle, Borick says.

Once that has died down, the institute will return to working on partnerships with local organizations like school districts and the United Way. In the spring, climate change polling will start up again, and students will begin some of the earliest surveys on the 2020 presidential race.

Long-term, Borick is considering the shifting technological landscape to see how the institute might evolve to continue conducting high-quality research. Currently, the institute only surveys select groups (like members of a community organization) online, because there’s no database of email addresses that could ensure random sampling in surveys of the general population. However, some challenges with phone surveys, per Ph.D. student Rogers, are that younger people are less likely to answer their phones and that a respondent might skew their answers due to biases they may have based on an interviewer’s voice.

The current best practice for conducting online surveys is called an “online probability-based sample, where we reach out to people via phone and mail (where everyone has a chance to be selected) and then have them complete surveys via a web-based platform,” Borick says. He is lobbying for changes in the coming years—including a new space—to allow the institute to conduct these types of polls.

Regardless of how the technology or the location changes, the institute will continue its original mission of focusing on the student experience—a mission that continues to inspire those who’ve worked at the institute long after they’ve left it. Niebler, who is collaborating with political-science colleagues at Muhlenberg and three other Pennsylvania colleges on exit polling this fall, looks back fondly on the sense of ownership she felt at the institute: “Borick’s ability and willingness to work with undergraduate students, to give them responsibilities and projects and to let them take the lead and do things of interest to them is what I hope to be able to do with my own students.”