“A Career-Changing Moment for Me as a Filmmaker”: Professor’s Project Receives Award From the Sundance Documentary Fund

In “Art After-Life,” Assistant Professor of Film Studies David Romberg employs generative AI technology to allow him to converse with his father, Latin American artist Osvaldo Romberg, posthumously. David has collaborated with Assistant Professor of Computer Science Hamed Yaghoobian as well as students and alumni on the project.By: Meghan Kita Monday, September 23, 2024 01:20 PM

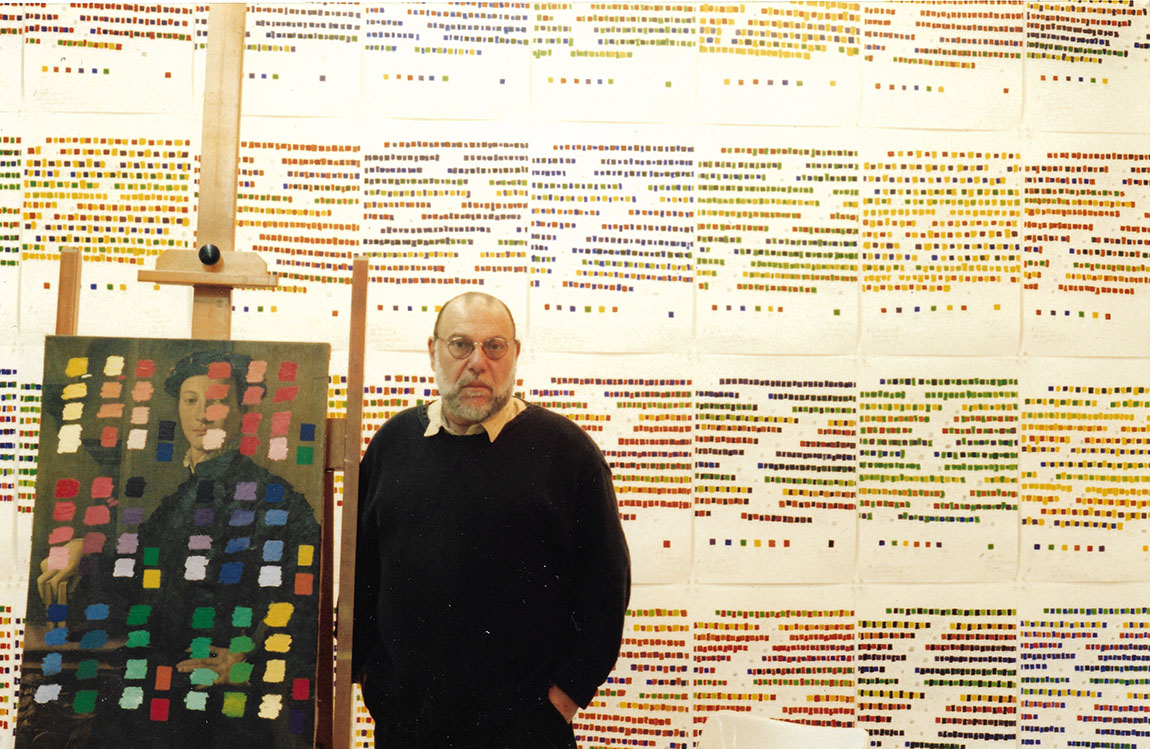

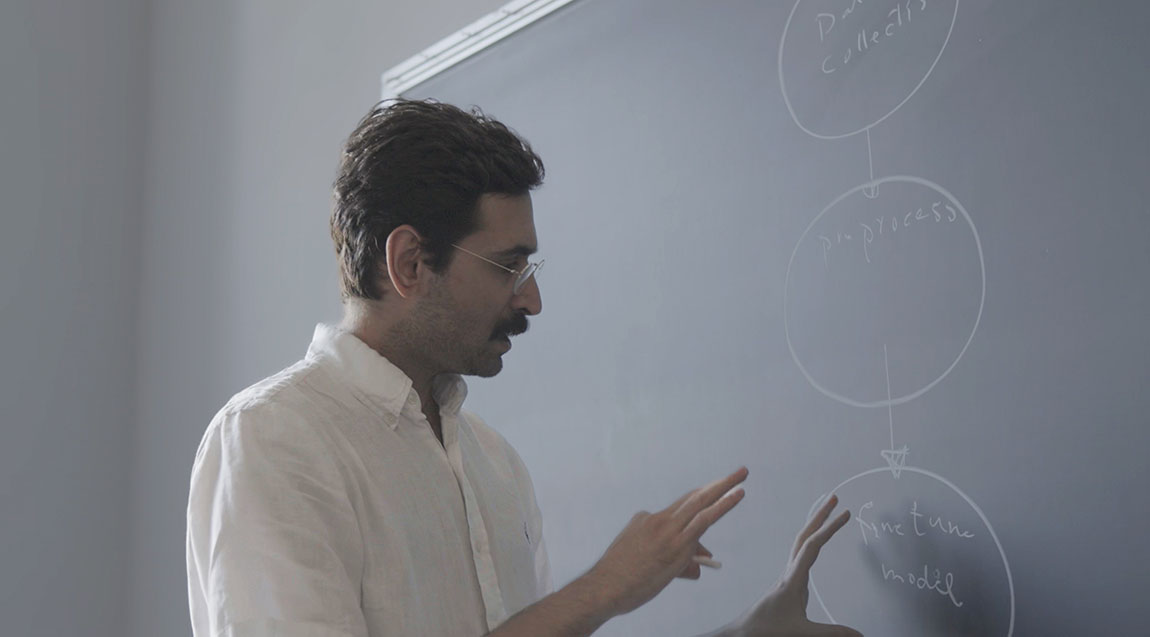

Assistant Professor of Film Studies David Romberg and Assistant Professor of Computer Science Hamed Yaghoobian during production of “Art After-Life.”

Assistant Professor of Film Studies David Romberg and Assistant Professor of Computer Science Hamed Yaghoobian during production of “Art After-Life.”In 2017, two years before he began teaching at Muhlenberg, Assistant Professor of Film Studies David Romberg began work on a documentary about his father, the avant garde artist Osvaldo Romberg. Osvaldo had been an influential artist in Argentina during the 1960s and early 1970s; he fled the country when it became a military dictatorship but continued to produce work that was exhibited around the world.

In 2019, just as David was starting at the College, Osvaldo was diagnosed with a fast-moving cancer. He underwent surgeries that impaired his ability to communicate, and the film was put on hold. Shortly after, as David flew to visit him over Thanksgiving break, Osvaldo died.

David interviewing Osvaldo for the original documentary project

“The film, which started out as a portrait of his life, really transformed into a film about grief and this idea of, ‘What happens when you don’t have closure when someone close to you passes away?’” David says. “I needed to find a creative way to reimagine what it would be like to have that conversation with him that I could never have.”

“Knowing that an organization like Sundance believes in the film and feels like it needs to be out there, that it needs to be seen — to me, that’s almost more important than the money.”

—Assistant Professor of Film Studies David Romberg

That reimagining became Art After-Life, a film that, in August, was awarded $50,000 from the Sundance Documentary Fund, a highly prestigious recognition in the film industry.

“For every filmmaker who’s making documentaries, [this award] is kind of like the holy grail,” says David, who has applied for Sundance funding many times before. “It feels like a career-changing moment for me as a filmmaker. … Knowing that an organization like Sundance believes in the film and feels like it needs to be out there, that it needs to be seen — to me, that’s almost more important than the money.”

David going through his father’s storage space after his death

Campus Collaborators

In the wake of his father’s death, David pored over Osvaldo’s archives — his artwork, writings and interviews. Osvaldo was a painter, but even during his time in Argentina, he was exploring the use of computer-generated images in his art. Osvaldo maintained a lifelong interest in the intersection of art and technology. As David considered the ethics of utilizing generative AI to have a final conversation with his father, he consulted with his family.

“The overwhelming feeling was that he would have used [AI] in his own work,” David says.

Through their work on Muhlenberg’s Committee for Faculty and Student Scholarship, David connected with Assistant Professor of Computer Science Hamed Yaghoobian, whose scholarly interests include computational ethics and who teaches a course called Human-AI Interaction. Yaghoobian agreed to be a collaborator on Art After-Life and to build the generative AI model, which they refer to in the film as a “transhumanist representation” of Osvaldo, using Osvaldo’s writings and voice recordings as source material.

“This project captivates me due to its exploration of profound themes such as grief, identity and the essence of human existence through the lens of transhumanism,” Yaghoobian says. “The endeavor isn’t about resurrecting Osvaldo per se, but rather about re-actualizing his intellectual and emotional essence. It’s a celebration of his life and legacy through ongoing dialogue and remembrance, facilitated by technology.”

A scene from the film featuring Yaghoobian explaining how they will build the AI model

David has also collaborated with students on the project; one of them, Joe Romano ’23, a film studies and media & communication double major, has continued to work on it after graduation, as an assistant editor and additional cinematographer.

“I went into this project knowing that it would take a lot of time and effort to make. I had wanted to collaborate with David for some time, and … I knew that being able to work with him on a film would be a valuable learning experience for me as well as being personally rewarding,” says Romano, who had the opportunity to assemble the very first draft of the film and share it with the project’s main editor, Carlos Cambariere. “I have learned so much from everyone along the way.”

“I had wanted to collaborate with David for some time, and … I knew that being able to work with him on a film would be a valuable learning experience for me as well as being personally rewarding. I have learned so much from everyone along the way.”

—Joe Romano ’23

Finishing the Film

The final scene of the film — the conversation between David and the AI model of his father — has yet to be shot. David and Yaghoobian are continuing to finetune the model, which will feature prominently in a memorial exhibit of Osvaldo’s work that will take place in October. The exhibit will include an installation that will allow the public to interact with the model, which uses a voice cloned from recordings of Osvaldo’s. The exhibit, too, will be part of the film, and David hopes to eventually bring the installation to Muhlenberg’s campus.

Osvaldo pictured in a series of photographs in which he classified his body according to a system of numbering

Art After-Life needs to be completed by mid-2025; one of its major funding sources is ITVS (Independent Television Service), one of the largest documentary distribution companies that strictly distributes on public access channels and platforms. However, if the documentary debuts on television, it can’t make its official premiere at a major film festival, a situation David is now working to navigate.

“Because we got [the Sundance award], we’re alumni of the [Sundance] program now, so it opens you up to other opportunities — funding opportunities, networking opportunities, and a whole support system that exists for your film until it’s done or even beyond,” David says. “We’re already thinking of submitting the film to the Sundance Film Festival; we’re in contact with them about that. We would love to premiere the film there.”

“Even though it seems that I’m on this journey to use technology to deal with my grief, what I’m experiencing is essentially an understanding that technology can’t solve something that is an existential human experience.”

—Assistant Professor of Film Studies David Romberg

Despite the fact that Art After-Life is not yet complete, it’s already clear to David what he hopes audiences will take away from it.

“Part of the idea of the film is that grief is something that can’t be fixed. It’s a void that can’t be filled with technology,” he says. “Even though it seems that I’m on this journey to use technology to deal with my grief, what I’m experiencing is essentially an understanding that technology can’t solve something that is an existential human experience.”