Open for Business

This innovation and entrepreneurship course requires student teams to actually execute their ideas.By: Meghan Kita Monday, May 13, 2019 09:28 AM

Students from UPCycle Apparel sell used clothing in Seegers Union. Photo by Sammi Singman '20.

Students from UPCycle Apparel sell used clothing in Seegers Union. Photo by Sammi Singman '20.If the five students who run the consignment clothing business UPCycle Apparel only had to write a business plan, they never would have built their own foldable clothing racks, contended with the challenges of finding space to hold their pop-up sales events or realized it’s easier to leave items on their hangers when transporting them.

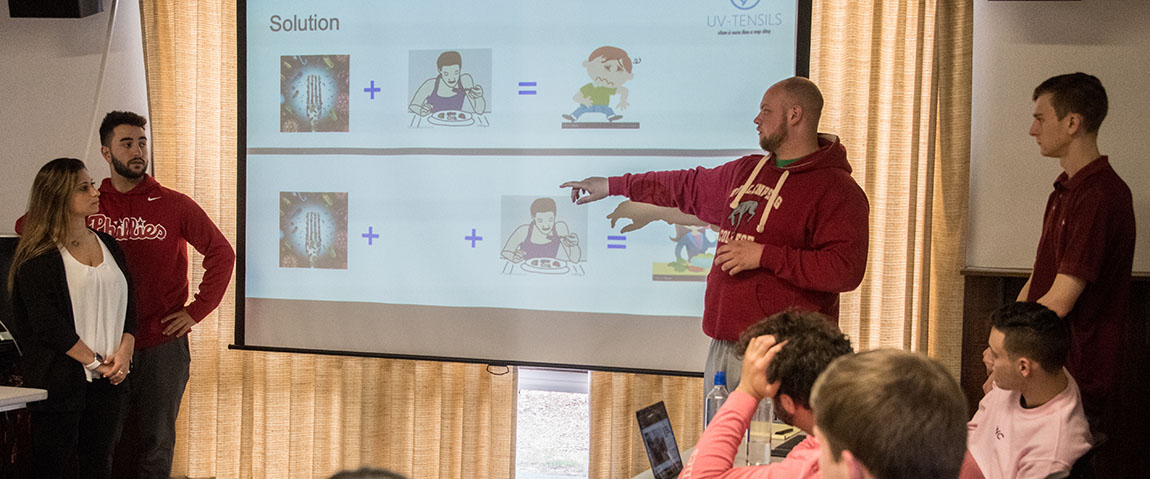

If the four students who invented a utensil-sanitizing case called UV-Tensils only had to write a business plan, they never would have created a working prototype, collected upwards of 40 presales or met with an attorney about design patents.

That’s why the teams in Rita Chesterton’s Business Plan Development class must launch a business first, with a goal of generating $200 in revenue by the semester’s end, and use what they learn from that experience to write a business plan.

“Writing a business plan about a theoretical business is way different from understanding what it takes to build an actual business,” Chesterton says. “It’s about making the students see how difficult it is, but how they’re capable of doing it.”

How the Class Works

Chesterton, the director of Muhlenberg’s Innovation and Entrepreneurship Program, modeled the course after one at the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul, Minnesota. That course resulted in Love Your Melon, a business that sells hats and other products to support children with cancer. Chesterton reached out to that course’s professor to get ideas for Business Plan Development, which she’s now taught four times.

This semester, she asked students to brainstorm business ideas over winter break to save time. When the class began, students broke into five teams (UPCycle Apparel; UV-Tensils; two clothing companies, Backbone and Oinc Streetwear; and a drop-shipping business, Magna Cart) and came up with business models. The course has no textbook, so some of the money students would have spent on that ($20 to $50 per student, on average) went into their businesses—an extra incentive to try to earn it back, and then some. Once the ideas were created, it was time to sell.

“That’s one of the most difficult parts of entrepreneurship: getting someone to turn their money over to you,” Chesterton says.

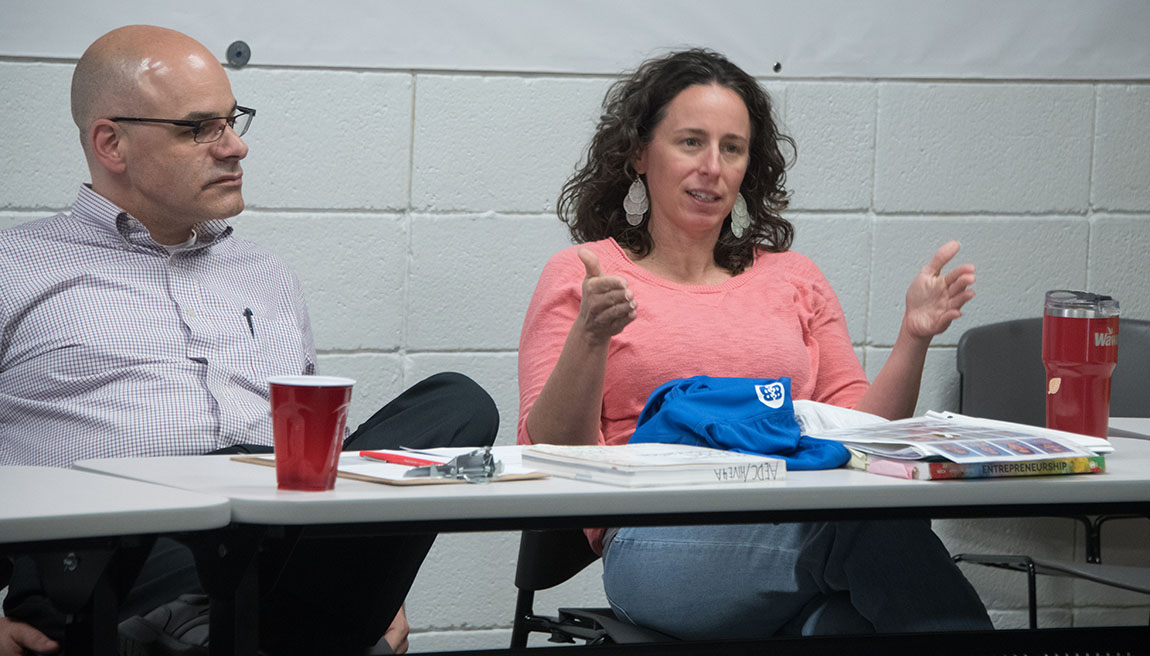

The class sessions include some lectures, some teamwork on the businesses and the occasional visiting expert. One guest this semester was Anthony Durante (pictured, with Chesterton) from the Allentown Economic Development Corporation. Each group had five minutes to present to Durante and 10 minutes to field his questions and feedback. The students benefit from outside perspectives like these: “It’s my role to be supportive as well as critical,” Chesterton says. “Sometimes it helps to have somebody who’s outside who can be more critical.”

Along the way, students write reflections every other week: They pick something discussed in class and relate it to their business, which helps Chesterton assess what they’re learning. And, new for this semester, students were required to use the laser cutter, vinyl cutter or 3D printer set up in Hillside House as they built their business.

The tools are part of a pilot makerspace Chesterton has created with Jordan Curtis ’21. He’s a student on the UPCycle Apparel team who’s also doing an independent study to determine how to open a permanent makerspace to all innovation and entrepreneurship students—and eventually to all Muhlenberg students.

“As an entrepreneur, you have to learn to do things you don’t know how to do,” Chesterton says. Using the makerspace “forces the students to struggle with something.”

By the end of the semester, Chesterton asks students to create a formal business plan, including how they might continue their businesses: How do you scale it up? What resources would you need to keep it going? What’s your vision for this business in three to five years?

“They can base it on some numbers and a real understanding of the product,” she says. “I always hope some team might be inspired enough to continue on with their venture.”

What Students Learn

Kiefer Cundy ’19, a neuroscience major with a public health minor, was inspired enough to consult with the owner of a product design and manufacturing company as well as an attorney about how to proceed with UV-Tensils. Cundy came up with the team’s idea after a long-term interest in the potential of advanced ultraviolet light technology, and he built the rough prototype (using the makerspace’s laser cutter) the team used to solicit preorders. Based on Cundy’s conversations, securing a patent at this time will be cost prohibitive, but creating a formal prototype that could be used to launch a Kickstarter campaign may not be. He and his teammates (pictured below) hope to have that completed by the end of August.

Curtis says the UPCycle Apparel group is weighing how they might proceed. Options they’ve discussed include finding a permanent space on campus, expanding their reach to include events at other schools and considering how they might turn clothing that doesn’t sell into something useful. These discussions are all inspired by the experiences they’ve had as they actually launched the business this semester.

“Coming up with a plan is really just the first step,” Curtis says. “The plan has to constantly change. Nothing can replace that hands-on experience.”