First-Year Seminar: The Next Pandemic

Students craft verbal and written arguments on topics surrounding the outbreak and spread of disease.Monday, November 27, 2017 00:36 PM

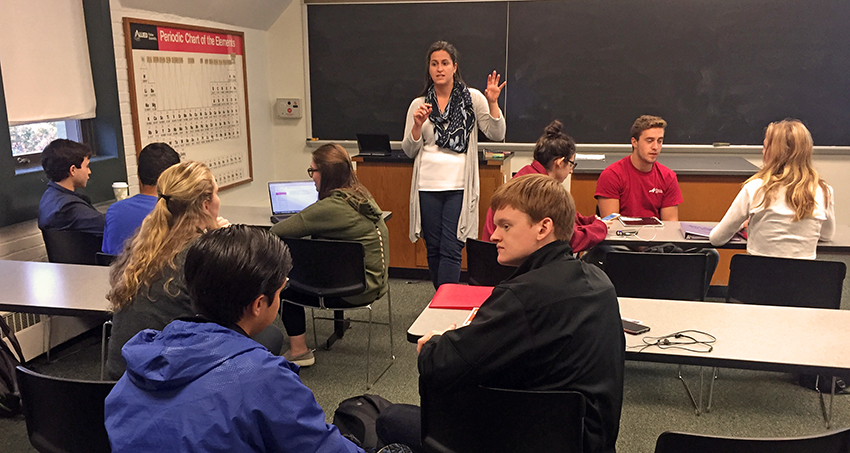

Biology lecturer Melissa Dowd (center) answers questions during a small-group discussion in her first-year seminar. Photo by Meghan Kita.

Biology lecturer Melissa Dowd (center) answers questions during a small-group discussion in her first-year seminar. Photo by Meghan Kita. This fall, staffers from the Office of Communications sat in on a number of first-year seminars to observe how Muhlenberg introduces its new students to college-level writing. Professors from a variety of disciplines design and teach the courses. Some select a topic that’s closely related to their academic specialty, while others choose something they’re personally passionate about. While the seminars vary widely in subject matter and structure, they all share the same end goal: to teach students to think critically and analytically when constructing an argument.

“The difference between high-school and college writing is less a matter of style than of attitude," says English professor Jill Stephen, who co-directs the Writing Program with fellow English professor David Rosenwasser. “Rather than framing a single argumentative claim and repeatedly demonstrating that it is ‘right,’ students in first-year seminars learn to treat ideas as hypotheses to be tested.”

The seminars are small—limited to 15 students each—and each one has a paid writing assistant, a returning student who has completed a credit writing theory course, attends all the classes and works with first-year students inside and outside the classroom to develop their writing skills. Thirty-three seminars are offered in the fall, with another eight offered in the spring. Here’s a glimpse at one of the seminars taking place this semester.

Melissa Dowd, a biology lecturer, performs a Google search, and an illustration of a young girl with a puffy, lopsided face appears on the screen in the front of the classroom. There’s a mumps outbreak at Syracuse University, and many of the students in this first-year seminar, The Next Pandemic, don’t really know what mumps is—evidence of the efficacy of childhood vaccinations in the United States. “A lot of times, anti-vaxxers don’t view diseases as life-threatening because we haven’t seen them because we’ve been vaccinating,” Dowd tells them. A student asks whether Syracuse is forcibly vaccinating, which segues nicely into that day’s writing exercise on a chapter of “Pandemic” by Sonia Shah that addresses responsibility and blame during outbreaks.

It’s the first time Dowd has taught a first-year seminar. “Writing is not my forte, so it’s been a learning process for me too,” she says. “Some of the things I see lacking in sophomores are the things I’ve tried to focus on,” like including super-long quotes because they’re afraid of plagiarizing and/or they’re looking to take up space. “I don’t give them a page count,” Dowd says. “I don’t want them to fill a paper with fluff that doesn’t mean anything when the paper would be so much more impactful at five pages instead of 10.”