First-Year Seminar: Do Robots Dream?

A toy older than the students observing it helps spark a conversation about the difference between claims and evidence.By: Meghan Kita Monday, December 11, 2017 04:44 PM

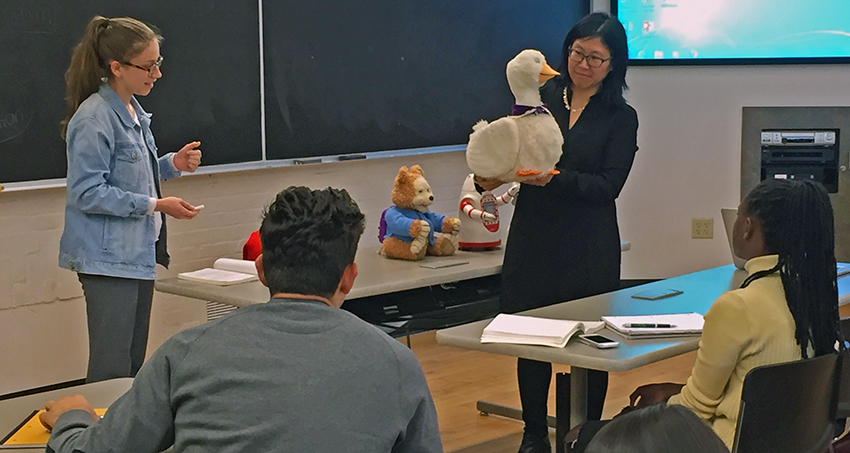

Writing assistant Olivia Garcia ’20 and professor Irene Chien lead the first-year seminar Do Robots Dream? Photo by Meghan Kita.

Writing assistant Olivia Garcia ’20 and professor Irene Chien lead the first-year seminar Do Robots Dream? Photo by Meghan Kita.This fall, staffers from the Office of Communications sat in on a number of first-year seminars to observe how Muhlenberg introduces its new students to college-level writing. Professors from a variety of disciplines design and teach the courses. Some select a topic that’s closely related to their academic specialty, while others choose something they’re personally passionate about. While the seminars vary widely in subject matter and structure, they all share the same end goal: to teach students to think critically and analytically when constructing an argument.

“The difference between high-school and college writing is less a matter of style than of attitude," says English professor Jill Stephen, who co-directs the Writing Program with fellow English professor David Rosenwasser. “Rather than framing a single argumentative claim and repeatedly demonstrating that it is ‘right,’ students in first-year seminars learn to treat ideas as hypotheses to be tested.”

The seminars are small—limited to 15 students each—and each one has a paid writing assistant, a returning student who has completed a credit writing theory course, attends all the classes and works with first-year students inside and outside the classroom to develop their writing skills. Thirty-three seminars are offered in the fall, with another eight offered in the spring. Here’s a glimpse at one of the seminars taking place this semester.

Irene Chien, assistant professor of media & communication, walks into a classroom in Trumbower with a tote bag full of toys. “Let’s get our friends back out,” she says to the students taking her first-year seminar, Do Robots Dream? The course explores how robots have been imagined in popular culture. Today, they’ll do an exercise called “10 on 1”: They’ll each make 10 observations about an object (in this case, a robot) and use that evidence to develop a claim.

Only one of the four toys Chien places on the table in the front of the room has the dome-like, faceless appearance you might picture when imagining a robot. The others are Yoda, TJ Bearytales and Mother Goose, which hides a cassette deck beneath its wing. The students choose Mother Goose as their muse. When writing assistant Olivia Garcia ’20 presses “play,” the goose’s beak opens and shuts as a hidden speaker emits a story and students take notes.

Olivia spearheads the discussion that day, helping students understand the difference between interpretive claims and concrete evidence. (For example, saying Mother Goose’s movements are “robotic” assigns a subjective quality to those movements, while observing that her beak moves out of sync with the voice on the tape does not.)

Occasionally, Chien chimes in to help illuminate common student errors, like choosing a thesis first instead of allowing observations to inform the selection of a thesis. She gives a hypothetical example of a student who may have decided Mother Goose was meant to be a comfort object before noting the creaking sound the toy makes as its head and beak move. “They say, “Well, it makes a screechy noise, but you can hardly hear it, so that doesn’t disprove my thesis,’” Chien says. Those complicating details do matter, she says, and can help the writer to develop a more nuanced and precise interpretive claim.